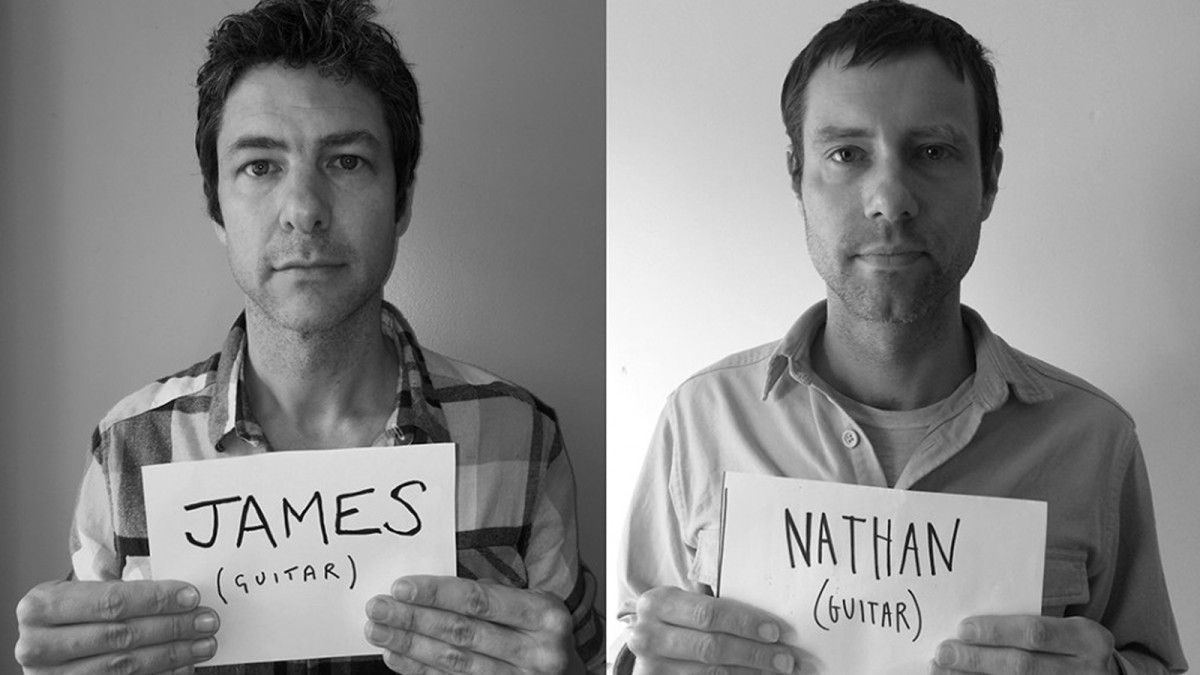

James Elkington & Nathan Salsburg

The second album of astonishing duets by guitarists James Elkington (who has toured and/or recorded with Jeff Tweedy, Richard Thompson, and Steve Gunn, among others) and Nathan Salsburg (an accomplished soloist deemed by NPR “one of those names we’ll all associate with American folk guitar”) is a sublime suite of nimble, filigreed compositions by two singular stylists. Belying its title—“ambsace” is the lowest throw of dice; snake eyes—the record thrives on a gentle empathy and generosity of spirit, sitting sneakily protean original compositions alongside gorgeous arrangements of songs by Duke Ellington and The Smiths at the same big hand-hewn table.

They say the only good thing to come out of Indiana is I-65 South. At least that’s how Nathan Salsburg heard it while growing up in Louisville, which receives the highway as it departs the Hoosier state and crosses the Ohio River into Kentucky. And if I-65 North actually left Indiana and made it as far as Chicago, where English-born James Elkington has lived for the past fifteen years, the joke could apply on his end too.

Be that as it may, it’s well known that of the five hours that connect Louisville to Chicago on the Eisenhower Interstate System, the four that bisect Indiana tip to tail and vice versa are among the most soul-bruising. Jim and Nathan can vouch for it; they’ve been making the drive for years: the former, when he and his wife (a childhood friend of Nathan’s) come to visit his in-laws in the Derby City, and the latter, when he goes to visit with Jim and family in Chicago. On either end, they’ll watch college basketball, hit the record shops, do some guitar playing. It was initially Jim’s idea for the two of them to do some guitar playing together, sharing as they did then and now a love for the traditional musics of James’ native isle (particularly as expressed by Bert Jansch and Nic Jones) and Nathan’s native state (especially in the hands of its darker practitioners like Banjo Bill Cornett and Roscoe Holcomb.)

Their first record, Avos (2010), was the not entirely anticipated product of this good idea. And after playing three shows in honor of its release, they returned to more typical pursuits: James, touring and recording with a small army of collaborators — Jeff Tweedy, Steve Gunn, Richard Thompson, Brokeback, Freakwater, Daughn Gibson, Kelly Hogan, Jon Langford, The Horse’s Ha, Eleventh Dream Day — and Nathan, as curator of the Alan Lomax Archive, as well as a solo guitarist (and accompanist to Joan Shelley) whom NPR has deemed “one of those names we’ll all associate with American folk guitar.”

Ambsace, their not entirely anticipated follow-up record, was from its inception an antidote to getting soft in the fingers; despite the playing done independently on both sides of I-65, both James and Nathan attest that there’s no guitaristic workout quite like playing with one another. (It’s a cheeky reference at that, as “ambsace” is a defunct term for the lowest roll of the dice; it’s also, perhaps more cheekily, something worthless or unlucky.) This second iteration of their twenty-finger collaboration achieves and sustains the limpid, architectural elegance and rakish formality suggested by the first album. Masterful miniatures like “Up of Stairs” and “Invention #4” strut out from the parlor with a spidery sense of swing, the cascading runs recalling the leaf-dappled play of sunlight on water (or on wine, or whiskey.) Elsewhere (e.g., “The Unhaunted Williams”; “Carrots”; “Rough Purr”), the intricate cross-currents of their duets liquefy and pool, demonstrating a mastery of restraint and space.

The record was composed and recorded in Jim’s attic studio over two late summer sessions, one year apart. Joined later by Avos alums Wanees Zarour (violin) and Nick Macri (bass), Elkington and Salsburg each brought in parts to be submitted to the experience, which was animated by plenty coffee before three, plenty beer after, with songs taking shape in some cases over many stifling hours (e.g., “Bee’s Thing”); in others, over a matter of manic minutes (e.g., “Stern and Earnest”). Tunes grew out of constituent elements assembled like a round of Jenga, with the occasional crash to the floor and outbursts of laughter. When the teetering edifice seemed complete, it was played till structural integrity was achieved and it sounded good enough to record. Their ten new compositions, plus the further inclusion of three covers—by Duke Ellington, Norman Blake, and the Smiths—offer an adequate representation of the influences brought to bear on the playing of Ambsace in particular, but also the players of Ambsace in general. When taken as the sum of it parts, “ambsace” in fact means a couple of aces.