Hurray For The Riff Raff

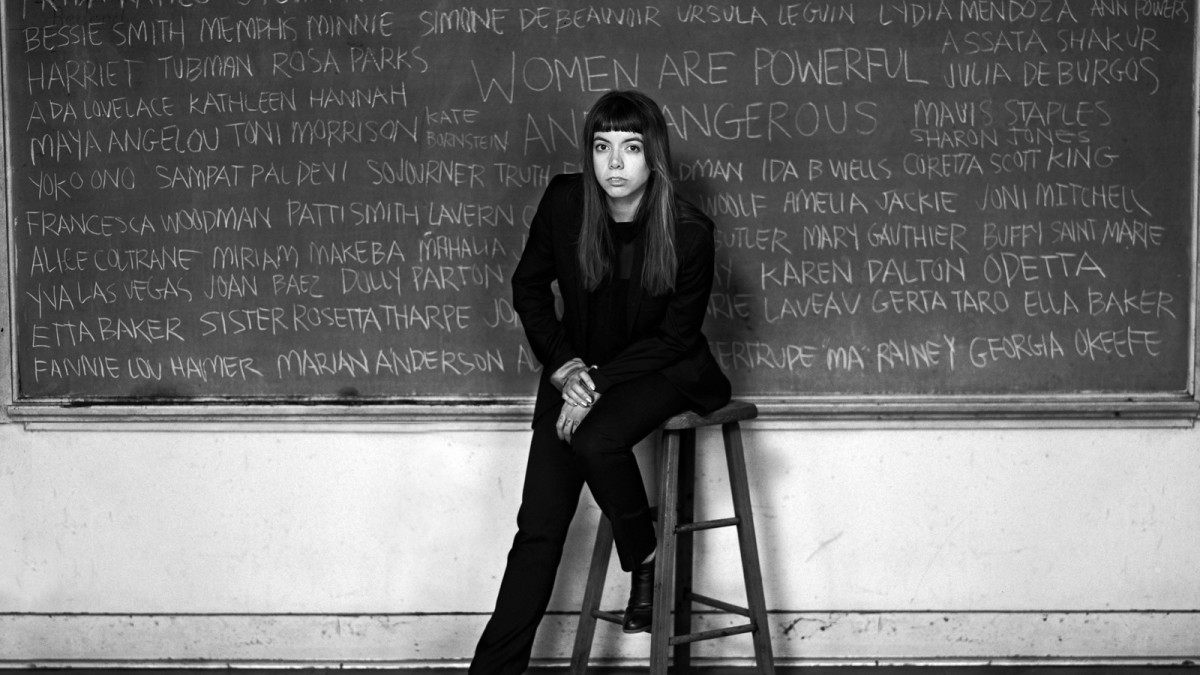

Hurray For The Riff Raff is Alynda Lee Segarra, but in many ways it’s much more than that: it’s a young woman leaving her indelible stamp on the American folk tradition. If you’re listening to her new album, ‘Small Town Heroes,’ odds are you’re part of the riff raff, and these songs are for you.

“It’s grown into this bigger idea of feeling like we really associate with the underdog,” says Segarra, who came to international attention in 2012 with ‘Look Out Mama.’ The album earned her raves from NPR and the New York Times to Mojo and Paste, along with a breakout performance at the 2013 Newport Folk Festival, which left American Songwriter “awestruck” and solidified her place at the forefront of a new generation of young musicians celebrating and reimagining American roots music. “We really feel at home with a lot of worlds of people that don’t really seem to fit together,” she continues, “and we find a way to make them all hang out with our music. Whether it’s the queer community or some freight train-riding kids or some older guys who love classic country, a lot of folks feel like mainstream culture isn’t directed at them. We’re for those people.”

Segarra, a 26-year-old of Puerto Rican descent whose slight frame belies her commanding voice, grew up in the Bronx, where she developed an early appreciation for doo-wop and Motown from the neighborhood’s longtime residents. It was downtown, though, that she first felt like she found her people, traveling to the Lower East side every Saturday for punk matinees at ABC No Rio. “Those riot grrrl shows were a place where young girls could just hang out and not have to worry about feeling weird, like they didn’t belong,” Segarra says of the inclusive atmosphere fostered by the musicians and outsider artists who populated the space. “It had such a good effect on me to go to those shows as a kid and feel like somebody in a band was looking out for me and wanted me to feel inspired and good about myself.”

The Lower East Side also introduced her to travelers, and their stories of life on the road inspired her to strike out on her own at 17, first hitching her way to the west coast, then roaming the south before ultimately settling in New Orleans. There, she fell in with a band of fellow travelers, playing washboard and singing before eventually learning to play a banjo she’d been given in North Carolina. “It wasn’t until I got to New Orleans that I realized playing music was even possible for me,” she explains. “The travelers really taught me how to play and write songs, and we’d play on the street all day to make money, which is really good practice. You have to get pretty tough to do that, and you put a lot of time into it.”

“The community I found in New Orleans was open and passionate. The young artists were really inspiring to me,” she says. “Apathy wasn’t a part of that scene. And then the year after I first visited, Katrina happened, and I went back and saw the pain and hardship that all of the people who lived there had gone through. It made we want to straighten out my life and not wander so much. The city gave had given me an amazing gift with music, and it made me want to settle there and be a part of it and help however I could.”

Many of the songs on ‘Small Town Heroes’ reflect that decision and her special reverence for the city. She bears witness to a wave of violence that struck the St. Roch neighborhood in the soulful “St. Roch Blues;” yearns for a night at BJ’s Bar in the Bywater in “Crash on the Highway;” and sings of her home in the Lower Ninth Ward on “End of the Line.” “That neighborhood and particularly the house I lived in there became the nucleus of a singer songwriter scene in New Orleans,” she explains. “‘End Of The Line’ is my love song to that whole area and crew of people.”

The scope of the album is much grander than just New Orleans, though, as Segarra mines the deep legacies and contemporizes the rich variety of musical forms of the American South for the age of Trayvon Martin and Wendy Davis. “Delia”s gone but I’m settling the score,” she sings with resolute menace on “The Body Electric,” a feminist reimagining of the traditional murder ballad form that calls on everything from Stagger Lee to Walt Whitman. She juxtaposes pure country pop with the dreams and nightmares that come with settling down with just one person in “I Know It’s Wrong (But That’s Alright),” while album opener “Blue Ridge Mountain” is an Appalachian nod to Maybelle Carter.

NPR has said that Hurray for the Riff Raff’s music “sweeps across eras and genres with grace and grit,” and that’s never been more true than on ‘Small Town Heroes.’ These songs belong to no particular time or place, but rather to all of us. These songs are for the riff raff.